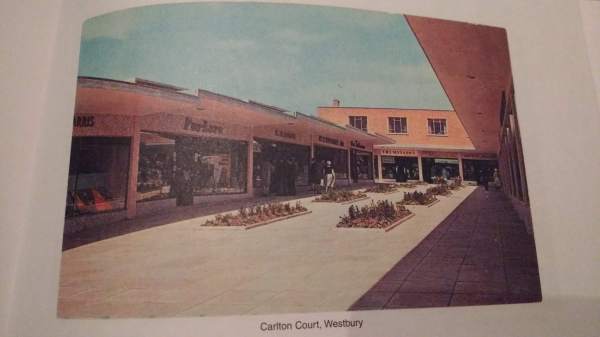

In 1999 the photographer Martin Parr published the book Boring Postcards, one of the most delightful art books I have ever seen. Far from being boring it is a nostalgia-infused catalogue of post-war Britain studied in terms of architecture, interior décor, leisure and holiday activities, commerce and infrastructure. Each page is a reproduction of a postcard with no additional textual information beyond the name of the building or location. Implicitly, the book tells a story of the urban redevelopment that took place through the 50s and 60s and, in the absence of an organising narrative of aesthetic or political contextualisation, the pictures have a strange dual quality, simultaneously familiar and odd.

The pictures that Parr has chosen for the book are necessarily all mundane sites: motorways, shopping centres, caravan parks. But it’s the fact that these sites were selected for commemoration on a postcard that gives the pictures such an odd feel. At one level, this oddness comes from the layers of irony that culture has accrued since the postcards were originally produced, and that accrual of irony itself maps onto the movement from modernism to postmodernism. In fact, the book’s charm comes directly from the clash between the modernism of the images and the postmodern context of its presentation. There is a naïve sincerity to the original intent of these postcards that seems hopelessly outmoded now. It’s not simply a question of nostalgia for lost futures, that is, a feeling of longing for the futures promised by movements such as brutalism and futurism.[1] Rather, Boring Postcards reveals a curious time in recent history when a very modern sense of urban living was being constructed. All those new shopping centres signalled a final end to the idea of rural self-sufficiency and heralded the final victory of commerce.

The first few postcards in the book are of motorways and they reveal the negotiation between the pastoral and the urban. Apart from the fact that the roads look quite empty it is striking how in some of these pictures the motorway seems to be a part of the landscape. The surrounding fields still seem to provide the predominant topographical character, the motorway itself looking like an old path that has grown organically into its current size. Somehow, there seems to be space for the coexistence of the road and the fields. And in a complementary fashion the newly built shopping centres and precincts seek to coexist with some sort of remembered idea of the rural. Each of them has trees or large planters dotted about in an admirable if vain attempt to provide some relief to the vistas of concrete.

The notion of an ambiguous interzone between the urban and the rural is captured by the concept of edgelands. First coined by Marion Shoard, the term edgelands refers to those in-between spaces created by urbanisation where space for nature still persists alongside cities, towns, shopping centres, motorways, canals, and so on. These zones sit between urban and rural areas, and they also sit uneasily between the two categories of urban and rural, often defying an easy definition. The edgelands have been much written about but they have never been entirely pinned down. It is in their very nature to be resilient and flexible, popping up in places where they are neither expected nor wanted, and often not really noticed.

In her classic essay on the subject[2], Shoard focusses on the edgelands that sit geographically between urban and rural areas, seeing them as a sort of no man’s land. This threshold status is an integral part of the edgelands’ character but they are not limited to these particular geographical spaces. In their book Edgelands the writers Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts consider the edgelands character of container yards, canals, airports, gardens and many other places that fit neither with a traditionally urban or rural definition. To some extent, this resistance to easy classification makes it possible to consider the edgelands as imaginative spaces encroaching upon and intermingling with other more readily classifiable areas. The ad hoc nature of the edgelands is described by Shoard:

“The edgelands are raw and rough, and rather than seeming people-friendly are often sombre and menacing, flaunting their participation in activities we do not wholly understand. They certainly do not conform to people’s chocolate-box idea of the picturesque. Tidiness is absent: no lawns here. If there is grassland, it is likely to be coarse and shaggy, perhaps grazed by a few sheep enclosed by derelict fencing. If ungrazed, it will be swamped by a riot of wild, invasive plants, fragments of tarmac, wrecks of cars and derelict buildings. We applaud the absence of litter in a landscape: the interface sucks in the detritus of modern life. Not only is litter and household waste casually dumped there, but formal waste-processing operations, such as car crushing, sewage treatment, or waste transfer are often deliberately located here, lest they despoil preferred environments. Edgeland rubbish tips may eventually be grassed over, but the cosmetic treatment of unsavoury artefacts is considered less necessary here than in either town or country.”[3]

As mentioned above, shopping centres and out of town retail parks are keen to bring some feel of nature into their purview with planted trees, bushes or plants. This may not sit entirely with the idea of edgelands because these are really more corporate garden spaces than edgelands proper. But this just highlights the fluid nature of the concept. But something that always hangs over the idea of edgelands is the question of ownership. These places often give the impression of being ownerless due to their state of deterioration but in other cases, such as the aforementioned retail parks, the impression is one of excessive and dulling control; a dash of nature merely as an appendage to the consumer experience. Ownership emerges as an important question either through neglect or fussy corporate management but once it enters into the discussion it raises some important issues.

And lying at the back of this question of ownership is the repressed trauma of the enclosure of the commons. This devastating, centuries-long process redrew the map of Britain both physically and psychologically. Much of the sense of dislocation that the idea of edgelands brings into play comes from the fact that these areas are often inheritors of ad hoc functions that have grown into being due to the unsettled lack of specificity of the spaces themselves. Their status is often one of an in-between place where much of the labour anterior to modern capitalism takes place. In some way that is rarely noted, the development from large areas of common land just outside habitations to the present edgelands landscapes that we see now is a major shift in the way that we position ourselves in relation to the land. The dispossession of the commons is a wound that has never healed and the odd, blinkered, uncertain ways in which we respond to edgelands spaces is a consequence of this loss of psychic confidence. This land is no longer our land, it is a utility for transient capital investment.

This question of ownership has been discussed recently with reference to urban environments. The increasing development of privately owned public spaces (POPS) is something that is a particular issue in London and other large cities but its implications are of wider importance. These areas appear to be public spaces but they are actually owned and regulated by private landowners. The question of ownership and function here is not so much one of ambiguity and liminality as is the case with edgelands spaces, but one of downright disenfranchisement. In a recent interview the architect Sam Jacob captured the sense of disjunction that these spaces seek to elide:

“There are developments where large parts of what was once public space have become privatised. Then developers essentially present part of it as a gift to the community, when it is exactly the opposite way around. Think of Elephant Park that Lendlease are building in Elephant and Castle. It is presented as a beautiful oasis of nature where children can play, wrapped up as some kind of incredible gift when actually it belonged to us in the first place. That sleight of hand is very disturbing.”[4]

Furthermore, the idea of urban enclosures has been mooted as a way of better understanding the process whereby capital accumulation is encouraged to proliferate, not just through land acquisition as was the case with the earlier enclosures, but also through the privatisation of functions that had previously been communally organised. In a paper exploring the notion of urban enclosure[5], Stuart Hodkinson extends the idea to include the privatisation of housing, the inescapability of wage labour and the ubiquity of consumerist thinking; in general, the ideological dominance of a process of appropriation and disempowerment. This continual reterritorialization of all aspects of human life by the forces of capital manifests itself as a generalised ennui, a feeling of displacement, anxiety and dissatisfaction but without an identifiable referent. It is what Mark Fisher referred to as Capitalist Realism. The ideological dominance of the project is what allows its processes to unfold in a way that is more or less hidden or, if they are seen at all, they will be parsed as natural processes.

Despite the elision of the processes of appropriation it is of course still the case that there are sites of antagonism and conflict as these changes play out. One interesting area to look at with regards to this is the meaning of graffiti in urban areas. Graffiti is often registered as pure vandalism in a way that is totally different to the way in which advertising imagery is usually registered. Both are transient and unplanned adornments to the architecture of a cityscape but advertising seems to be naturally the more legitimate of the two. Think for example of the controversy surrounding Sadiq Khan’s move in 2016 to ban ‘body shaming’ advertising posters on the London Underground. Khan’s intervention brings in to play all sorts of issues surrounding the question of representation that are beyond the scope of this essay. But the important point is that there is an assumption that advertisers have a right to populate our public spaces and imaginations with imagery in a way that other image makers, such as graffiti artists do not. The actions of an artist like Banksy do not undermine this argument because his work has now become so much a part of the art world that it is welcomed and supported by local councils and other institutions wherever it appears. In other words, it fails to challenge the assumptions about the role and purpose of visual objects within cities. Its successful position within the world of capital (as ‘art objects’) confers on the work its supposed legitimacy and its status is widely registered as a work of high value public art rather than vandalism.

In any case, it is beyond doubt that the conflict over the means of visual expression within cities has been won by the corporations whose changing visual landscape is a significant part of the experience of living in a city. Many cities are now approaching the look of the 2019 city as depicted in Blade Runner. The role of visual culture in a municipal sense is mostly confined to the interiors of buildings (art galleries) although some public art still exists. But the dominant visual impression apart from architecture is that provided by advertising. In a way that mirrors the movement from common land to edgeland, the visual culture of city centres has moved from municipal public art to corporate advertising.

Mark Fisher argued that the nature of a city determines the type of artistic creation that can take place there. The form of economic labour and the very real ambience created by the form of buildings and thoroughfares keys in directly to the possibilities for oppositional artistic projects:

“As Jon Savage points out in England’s Dreaming, the London of punk was still a bombed-out city, full of chasms, caverns, spaces that could be temporarily occupied and squatted. Once those spaces are enclosed, practically all of the city’s energy is put into paying the mortgage or the rent. There’s no time to experiment, to journey without already knowing where you will end up. Your aims and objectives have to be stated up front. ‘Free time’ becomes convalescence. You turn to what reassures you, what will most refresh you for the working day: the old familiar tunes (or what sound like them). London becomes a city of pinched-face drones plugged into iPods.”[6]

Certainly, this is a familiar counterblast against neoliberalism, and the prospects for a fundamental reconstitution of the nature of cities like London into something more attuned to the spirits of ’67, ’77 or ’87 seems remote and counterintuitive. The cities are turning into something else entirely and the society of control is in the ascendency. But rather than work towards such a reconstitution of cities as the primary locus for an art that subverts the predominant path of social development, why not look instead to the edgelands as places where such a project of subversion might begin? It is in the nature of edgelands that they tend to be located either on the fringes of towns or running through them in quasi-hidden corridors or clumps. These types of spaces, which emerge as either functional zones of mere utility or remain simply overlooked altogether, already have a subcultural, occult flavour to them. They retain something of the lost pastoral of our rural past but they also gesture towards the lost futures of modernism. In this liminal, Janus-like territory, there may be sought a temporary suspension of the contemporary codes of living.

In some ways, the edgelands have already taken on something of this character but sadly in a rather negative respect. Places like canal towpaths, industrial estates and railway sidings are already locations for sex attacks, prostitution, dogging and murder. The lowest and most unmediated impulses have found their place in the edgelands. But the task for us is to recognise that the edgelands themselves only attract those sorts of behaviours at the moment because they exist in some way outside of the timeframe of the city and also outside of its mores. Traditional folklore often draws upon murder, rape and other such personal tragedies for its subject matter and the edgelands currently provide the lawless backdrop for such crimes.

This is not at all to suggest some sort of cynical exploitation of others’ personal misery for the purpose of creating a new folklore. Rather it is an attempt to confront the fact that such unregulated, repressed impulses are necessarily finding the edgelands to be their natural ground, and that this is because the edgelands have not undergone the same processes of systematic appropriation that the commons underwent in the past and that the cities are undergoing now. The edgelands are to some extent overlooked and this has meant that they attract lawless forces. True, the way in which such lawless forces have been drawn to edgelands locations so far has often involved mundane and unpleasant behaviours, but a lawless zone should be a fertile ground for imaginative exploration. The edgelands are the natural place for a countercultural, subversive and radical praxis of artistic and ritual refusal to take place in, whether physically or imaginatively. There should be a concerted effort to claim the edgelands as a zone of autonomous artistic freedom wherein the beginnings of a new folklore should be formulated.

The edgelands have always invited rites of passage to take place within their purview, whether such rites are sexual, violent or whatever. Due to the fact that they sit outside of society’s lines of sight they can be very sinister places. What we should be aiming towards is a formalisation of these rites so that they do not take place in a purely instinctive, random and nihilistic fashion. Instead they should take place with conscious intent, directed towards a particular goal. Instead of illicit fucking, sexual magick; instead of vandalism, occult Merz-actions; instead of graffiti, runic sigils. As already mentioned, this may be either a literal enactment in the edgelands themselves or it may be a channelling of the energies into an imaginative creation using the edgelands as a backdrop. This might involve painting, film making or fiction. The point is to utilise the proximity of this liminal space in order to challenge the increasing homogenisation and commercialisation of modern life.

From the early medieval period through to the beginnings of industrialisation there were boundaries that marked the edge of the village or town. Beyond these boundaries there was a dangerous, wild zone where the nightmares of the community were incubated and born as the monsters and supernatural entities of folklore. Since the completion of the post war infrastructure projects that are documented in Boring Postcards, such as motorway building, we have enjoyed increased mobility, and consequently we have pretty much erased the concept of distinct borders around our communities. The road network has joined distant places together and an unintended consequence is that the notion of an outside to the community has been delegated to the edgelands areas. The edgelands have taken on the character of the vast wooded areas of Britain that used to separate different parts of the country. And, where once we would fear going astray in the woods, we must now face the sinister aspect of the edgelands and begin to populate them with the denizens of a new folklore.

- For more on Lost Futures see Fisher, M. (2014). Ghosts of My Life. Winchester: Zero Books.

- Shoard, Marion (2002). “Edgelands”. In Jenkins, Jennifer. Remaking the Landscape. London: Profile Books.

- Shoard, M, 2000. Edgelands of Promise. Landscapes, 1(2), 74-93.

- Lobb, A. and Jacob, S. (2018). How the Bright Housing of the Future Became a Relic of the Past. The Big Issue, (No. 1309).

- Hodkinson, S, 2012. The New Urban Enclosures. City, 16(5), 500-518.

- Fisher, op. cit.

Boring Postcards by Martin Parr

Edgelands by Paul Farley and Michael Symmons Roberts

An interesting essay covering a topic dear to my heart,but Sam Jacobs needs to learn the difference between “public” “publicly-owned” and “private”….I would challenge anyone to give me an example,in the London area,of a piece of land that was once public,but is now a POPS.

That is not to imply that there is no issue here,but rather one of being strictly accurate.

LikeLike